CUBA'S TIN PAN ALLEY

1947

[LIFE

magazine 6 October 1947 pp. 145-48, 151-57]

CUBA'S TIN PAN ALLEY

From Havana's shabbiest cabarets and voodoo lodges pours

an endless

flood of sultry rhythms, which are danced to all over the

world

By: WINTHROP SARGEANT

Page 145

In 1930, on the heels of the stock-market crash, a wailing,

bombilating

Cuban tune called The Peanut Vendor hit Broadway and set

America's feet

and hips squirming in the intricacies of a new dance-the

rumba.

The significance of this event in the history of U.S. mores

at first

seemed slight. Prognosticators noted the trend,

attributed it to

depression-frayed nerves and gave it a year or so to peter

out.

But in the course of a decade the rhumba had not only shown

that it was

here to stay, it had become the basis of a huge American

industry. Latin-American dance bands equipped

with

maracas

and

bongos

elbowed U.S. jazz bands in nightclubs and ballrooms from New

York to San Francisco. Rumba specialists like

Xavier Cugat

made

fortunes in Afro-Latin rhythm. In one year (1946)

Americans paid

Arthur Murray nearly $14 million to teach them the

dance. Rumba

enthusiasts still account for more than 60% of his enormous

business.

The Peanut Vendor, which started it all, was followed by a

steady

stream of similar Cuban song hits, which began nosing the

conventional

American fox trots from their top positions on Tin Pan

Alley's

best-seller lists. Small Cuban farmers neglected sugar

cane and

tobacco to raise gourds that could be manufactured into

maracas.

Music began to rival sugar, cigars and rum as one of Cuba's

leading

exports, and the American man in the street, buying it in

vast

quantities every time he got near a juke box, became its

leading

consumer. Of all the popular music played today over

the U.S. air

waves, on juke boxes and in Hollywood movies, approximately

20% is

Latin-American, and nearly all of that 20% comes from the

small island

of Cuba.

Though Cubans are gratified by this increasing demand, they

are quick

to point out that there is nothing new about their trade in

musical

exports. Economically Cuba may be just another

Page 146

so-called

banana

republic. Politically it may be a hotbed of

tropical instability. But musically it has rivaled New

York as

the popular musical capital of the Western Hemisphere for

nearly a

hundred years. Little Cuba's amazing influence on the

world's

popular music started in the early 19th Century when an

itinerant

Spaniard named Sebastian Yradier settled in Havana, listened

to the

languid, cajoling tunes of the natives and wrote a tune

called El

Areglito. El Areglito became the first habanera.

Imported

to Spain, the habanera became a standard feature of Spanish

folk music,

and a generation later Georges Bizet wrote one that would up

as the

most popular tune in France's most popular opera,

Carmen. Yradier

followed up El Areglito with the old Cuban favorite La

Paloma, which

was commissioned by Mexico's Emperor Maximilian and has

served as a

model for Latin-American tunes for three generations.

Somewhere

in the 19th Century, according to scholars, Cubans also

invented the

tango, which they exported to Argentina, giving the

Argentinians what

has since become their most characteristic form of national

folk

music. The rumba and the conga came later. But

these are

merely the most notable of Cuba's recent musical

contributions to the

world. For home consumption Cubans produce a

clattering

assortment of sons, guarachas, danzons, puntos and boleros

that still

keep the hot Havana nights in a continuous uproar of

melody. The

curious thing about all this Cuban music is that there is

nothing

generically Cuban about it. Its music is written and

played in a

hybrid musical language that is part Spanish and part

African

Negro. Its melodies usually echo the sultry songs that

were

brought to Cuba from Latin and Moorish Spain. Its

rhythms are

descended from the tom-tom beats of the African jungle.

It thrives on bullets and marijuana

UNLIKE sugar and tobacco Cuban music is raised in the

streets of Havana

by a swarming, polyglot underworld that sings, drinks and

starves with

impartial exuberance. It grows in brothels, taxi-dance

halls and

clandestine voodoo lodges which upper-class Cubans persist

in regarding

darkly as temples of human sacrifice. Many of its

tunes are

created on borrowed pianos, some of them by bullet-scarred,

marijuana-smoking characters who sell them for the price of

a swig of

rum. They are tried out in the ram-shackle cabarets of

Las

Fritas, a street

[To see a full size photo,

right click and VIEW IMAGE]

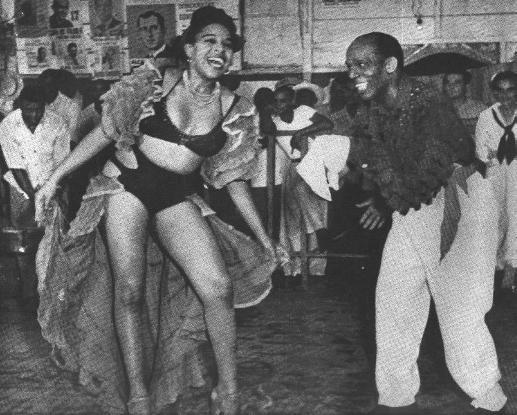

In Las Fritas Nightclub,

dancers Clara and Alberto Render

[dance the] traditional Cuban folk dance called "Shoeing

The Mare"

[To see a full size photo,

right click and VIEW IMAGE]

In Las Fritas Nightclub,

dancers Clara and Alberto Render

[dance the] traditional Cuban folk dance called "Shoeing

The Mare"

of Coney Islandlike concessions at nearby La Playa, where

Havana's

Negroes spend their nights out. From Las Fritas these

tunes sweep

into downtown Havana, where their whacking, clattering

accompaniments

are toned down for the tourist trade in expensive cabarets

like the

Chanflan and the Faraon. With luck and promotion by

the music

publishers of Havana's chaotic Tin Pan Alley, they may reach

the ears

of American bandleaders and catapult their authors into

international

fame. More often, however, they lose themselves in the

seething

uproar of Havana's night life, sinking downward

Page 148

like Havana's prostitutes, from high-class nightclubs to 6¢

creep

joints, and die out, making room for younger and fresher

tunes.

At Las Fritas one of the more recent hits is a jumpy little

tune known

as Penicilina (Penicillin), which celebrates the curative

properties of

what, in free and easy Havana, is a particularly useful

drug.

Penicilina's words automatically preclude widespread

international

popularity:

I carry you from limb to limb

As Tarzan carries beautiful Juana,

Because I took penicilina [Penicillin] and cured myself.

Try it and you will find out.

Chorus:

What is this, what is this?

How bad I feel.

To him who is lovesick, I say.

To him who is lovesick, I say

That penicilina can cure you.

Try it and you will see.

*1945 PEER INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION (USED BY PERMISSION)

Penicilina has several other versions, the most popular of

which has no

words at all and is sung with flashing eyes and

uncontrollable hips to

the illuminating text: "Bum-bum, bum, bum-bum, bum."

Its

repetitious six-note melody is underpinned with a thumping,

rattling

accompaniment that sounds like the forcible destruction of a

warehouse

full of cutlery. Invited to make a recording of it,

its author, a

genial Negro named Abelardo Valdes, embarrassedly included a

stanza of

Mendelssohn's Wedding March to fill it out to standard disk

length. Its local popularity finally achieved such

proportions

that Valdes was moved to turn out a second ditty called

Sulfatiasol. "My friends," he announced triumphantly,

"tell me I

should open a drugstore."

The object is not money

PENICILINA" was obviously not written with a canny eye

toward U.S.

commercial possibilities. The prevalence of tunes of

its type

causes the more enterprising of Cuba's music publishers to

throw up

their hands in horror. Although the better-known Cuban

composers

have an organization like America's ASCAP, the lamentable

fact is that

the balance of Havana's exuberant song writing industry is

carried on

not for money but for fun by its obscure and impoverished

composers. Various attempts to organize them on a

sensible,

businesslike basis have ended in abject failure.

Page 151

Such efforts at economic betterment as have occurred amid

the

prevailing aura of marijuana and indigence have been

sporadic and

highly individualistic. One of these erupted last year

when a

big, flashily dressed Negro named Chano Pozo became obsessed

with a

hunger for a new Buick convertible. Pozo, whose

masterpiece was a

ditty called El Pin Pin, had achieved some fame on the side

as a dancer

and a player of the big African conga drum. He

approached his

publisher, one Ernesto Roca, and demanded an extra thousand

dollars as

an advance on a new song. Roca refused and

Chano Pozo

assaulted

him. Like all prudent Havana music publishers, Roca

had an armed

bodyguard who promptly pumped four bullets into Chano Pozo's

midriff. Slightly inconvenienced, Pozo spent two weeks

in a

hospital, recovered and managed a down payment on the Buick

without

Roca's help. A few months later Pozo courted death

again, this

time as the breakneck driver of his new Buick. The

Buick was

wrecked, but Pozo escaped. He is still the toast of

Havana's

nightclubs and radio stations.

The homicidal musical limbo of Havana floats somewhat

indeterminately

between two other worlds. One is the heaven of

international

success, money, New York nightclubs and Hollywood fame to

which good

Cubans sometimes go in spite of themselves. The other

is the

underworld of African Cuba. And African Cuba is both

musically

and spiritually an outpost of a jungle civilization whose

headquarters

are still near the Niger and Congo rivers across the

Atlantic. In

this underworld African tribal dialects mingle curiously

with mangled

Spanish. Even today old Negroes are to be found in

Cuba who

regard themselves as temporary exiles and who, when asked

their

nationality, describe themselves not as Cubans but as

transplanted

Yorubas, or Araras. Their tribal organizations,

complete with

religious rituals, music, medicine and magic, are a mild

source of

worry to the Cuban authorities, who regard them as a

potential

political menace. Under the dictatorship of Machado,

which ended

in 1933, satirical political ditties from the jungle caused

frequent

unrest, and more than one Negro songwriter disappeared with

a price on

his head.

Its rhythm comes from African jungles

TWENTY percent of the Cuban population is African, and much

of the male

portion of that percentage is affiliated with a vague

organization

known to Cubans as Los Nanigos, which has existed ever since

colonial

times. Upper-class Cubans sometimes frighten their

children by

telling them the Nanigos will get them if they are not

good. The

Cuban police keep Nanigo tribal rituals under surveillance

and are

ready to pounce the minute there is a change from harmless

voodoo to

political agitation. Once a year, at carnival time,

the Nanigos

come into the open as the big event of the Cuban

comparsas. Their

value as a tourist attraction is undeniable. For five

successive

Saturday night the streets of Havana stream with joyous

throngs of

fantastically costumed Negroes, prancing along to drumming

and chanting

that sounds as though it came straight from the heart of

Africa.

But when the comparsas are over the Nanigos go back to their

slums and

farms. The big conga drum, which occasionally makes

its

appearance during the

page 152

carnival, reverts to the status of an illegal

instrument. It has

been outlawed except during fiestas for a good reason: the

conga drum

has been used as a jungle telegraph, roaring out secret

messages from

town to town in the Cuban hinterland and from neighborhood

to

neighborhood in Havana.

With few exceptions the instruments of Cuban music are

constructed on

native African models and are unquestionably the most

primitive ones

that have ever been used in civilized music. The Cuban

Negroes

make them out of dry gourds, hoe blades, old cutlery,

skeletal remains,

tree trunks, discarded cowbells and goatskins. But

their

manufacture for the export market has now become a

standardized

industry. Even the exotic

quijada, which

is made out of the

tooth-bearing jawbone of a horse, is now manufactured

according to

strict specifications. The Havana musical instrument

firm of Jose

A. Solis, which supplies many of the world's foremost

quijada

virtuosos, lists the instrument with the following note "[

The quijada]

is composed of the inferior maxilar of native horses about 2

years old,

prepared in such a manner that when struck with the fist

produces a

peculiar vibration very original and solely of this

instrument.

Dimension are: 14 in. long. Weight 1,250 grs."

The indispensable trademark of all rumba bands is, of

course, a pair of

maracas,

or gourd rattles, which are shaken with unremitting

enthusiasm

by a musician who devotes his entire career to the

craft. Closely

related to these are the guiros, or "nutmeg graters," –long

gourds with

corrugated surfaces which are scraped with a nail or bit of

wood and

emit a sound somewhat like the continued cranking of an

outboard

motor. A pair of

bongos, or large

drums made of hollow tree

trunks and calfskin and thumped with the bare hands, is also

to be

considered standard equipment.

A large rumba band is incomplete without at least one big

conga drum,

which is made of either a hollow tree trunk or an old

barrel. A

very high-class rumba band may also contain a marimbula – a

large

boxlike instrument with a series of metal tongues attached

to it.

When plucked with the fingers like the tongue of a jew's

s-harp, these

strips of metal give forth a powerful twanging sound

resembling that of

a bull fiddle. The marimbula is a common instrument in

the

Belgian Congo. The Nanigos make it out of old boxes or

suitcases

and discarded clock springs. Cowbells [

pico] and Chinese

wood

blocks [

claves]

may be added. So may a large earthenware jug

called a botija, which is precisely the same instrument as

that used by

old-time American Negro jug bands. One notable feature

about all

these instruments is that none of them, except possibly the

marimbula,

is capable of carrying a tune. In the primitive

backwoods

ceremonies of the Cuban Negroes this deficiency is filled,

if at all,

by the human voice. In the rather prim-sounding

danzons of

Havana, flutes and guitars often provide the melody.

But in rumba

music as Americans know it, the percussive symphony of the

primitive

Cubans is drowned in a standard orchestration of violins,

pianos,

accordions, saxophone, trumpets and so on.

Such refinements are the price paid for civilization.

The

primitive Nanigo can make music out of practically

anything. One

of his favorite instruments that has, as yet, failed to

appear in

standard nightclub bands, is the door. To play the

door, you

remove it from its hinges, rest one end of it lightly

against your

knees and pound it deliriously with both fists. The

result is

extremely sonorous.

Cuba's No. 1 composer

AT the opposite end of the Cuban musical spectrum from

door-playing is

the lucrative art of composing Cuban music for the

international

market. And in this art Cuba has produced a large

handful of the

world's most popular composers. One of them was the

late

Moises

Simons, who won himself a permanent place in history

by writing the

famous Peanut Vendor. Another is

Eliseo Grenet,

nightclub owner

and dean of Cuban bandleaders, whose pro-African Cuban

Lament so

enraged the Cuban dictator, Machado, that he had Grenet

chased all the

way to Barcelona, Spain. Grenet's masterpiece is the

popular tune

Mama

Inez. The undisputed king of Cuban popular music

is,

however, a mild-mannered, melancholy looking man named

Ernesto Lecuona.

Lecuona is a unique phenomenon in the world of popular

music.

Mention his name in any random gathering of Americans and

the chances

are you will draw a blank. But you will seldom meet an

American

who is unfamiliar with his durable song hits. Some of

them are

such old familiar tunes that people are always attributing

them vaguely

to some long dead classical composer. Other tunes

Page 154

are constantly nudging the top numbers on each year's hit

parade.

Still others are genuine classics familiar to every aspiring

piano

student. Among a list of some 300 compositions that

Lecuona has

turned out during the past 40 years, the most universally

known is

probably the sultry song Siboney, which is sometimes

jokingly referred

to as the Cuban national anthem. It is closely

seconded in

popularity by the ubiquitous piano pieces Malaguena and

Andalucia (The

Breeze and I), and by an enormous sheaf of popular songs

(Say ‘Si Si,'

Always in My Heart, Noche Azul, Two Hearts That Pass in the

Night,

Maria My Own, Jungle Drums, I'm Living from Kiss to Kiss and

so on)

that are played and sung in nightclubs, ballrooms,

restaurants, ball

parks, bars and broadcasting studios from Alaska to Tierra

del Fuego.

In the song-publishing houses of Manhattan's Tin Pan Alley,

Lecuona's

compositions are known as "standards," or perennial

best-sellers.

Where the average Tin Pan Alley hit has a life of a few

months,

Lecuona's tunes go on selling for decades. Siboney has

been

recorded by every major record company two or three times

over and is

still going strong. Say ‘Si Si' has sold almost a

million copies

in the U.S. alone. Malaguena, with a steady sale of

100,000

copies a year since 1931, has set something of a record in

the catalogs

of its New York publisher. In arrangements for

everything from

brass band to piano accordion, it is the most consistent

best-seller in

the U.S. It has even passed the durable record of what

was

previously the all-time champion in long-term U.S.

popularity, Paul

Lincke's death-defying, 45-year-old classic, Glow Worm.

He takes his admirers with him

LECUONA is a large unquenchably good-natured

51-year-old Cuban with

tobacco-brown eyes and small vocabulary of infra-Basic

English.

He commutes indefatigably between a cluttered apartment in

Havana and a

suite in a midtown New York hotel. Despite an untiring

effort at

sartorial elegance, he looks (as his friends are continually

pointing

out) exactly like Comedian

Zero Mostel.

A distinctly sedentary

type of man, he is nearly always to be found slumped

wistfully in an

easy chair, surrounded by a chattering g roup of loudly

dressed Latin

admirers who follow him wherever he goes, eating his food

and drinking

his liquor in unlimited quantities. Lecuona himself

seldom

touches a drink. He regards this portable bedlam with

an absent,

preoccupied air, occasionally rising with an apology to go

to a nearby

piano and thump out a few tunes over the din of

conversation.

"After all," he explains defensively, "a man ought to be

able to play

piano in his own house."

Though his royalties are calculated in the tens of

thousands, Lecuona has none of the characteristics of a man

of wealth, except

Page 157

perhaps his rather absent-minded indifference to

money. He is

constantly giving away small sums to assist aspiring maracas

players

and cabaret singers, American as well as Cuban. Over

the years

the total of these gifts is undoubtedly immense.

Lecuona is such a celebrated figure in Latin America that

when a man

named Ricardo Lecuona was killed in a Colombian airplane

crash, radio

stations in Mexico, Chile, Peru, Brazil and Argentina went

off the air

for a silent minute of mourning under the mistaken

impression that it

was Ernesto who had been killed. Five years ago

ex-President

Batista of Cuba named him cultural attache to the Cuban

Embassy at

Washington. As foreign propagandist for Cuba's native

music he

ranks second only to the redoubtable Spanish bandleader,

Xavier

Cugat. His unofficial career as Cuba's No. 1

musician, which has

recently culminated in half a dozen scores for Hollywood and

Latin-American movies, started in the cabarets and

silent-movie houses

of Havana. As a child of 11 he had already borrowed a

pair of

long pants and organized his first orchestra. A

two-step called

Cuba y America, which he composed at that early age, is

still in the

standard repertory of Cuban military bands. His first

big

international success arrived in 1922, when he toured

America and

appeared for eight consecutive weeks at the Capitol theater

in New

York, introducing his Malaguena and Andalucia to U.S.

audiences.

While Malaguena and Andalucia were typical Spanish-style

"salon pieces"

which might easily have been turned out by Latin composers

on either

side of the Atlantic, Siboney, which he introduced in 1927,

sounded the

typically Cuban note that was to infect U.S. dance

enthusiasts with the

rumba epidemic. The whole epidemic, as Cubans have

since

frequently pointed out, was based on a monstrous

misconception.

Siboney was not a rumba at all. Neither is The Peanut

Vendor. The mistaken and lucrative idea that they

were,

germinated in the head of the canny Tin Pan Alley Music

Publisher

Herbert E. Marks, who has since become the largest importer

of

Latin-American music in the U.S. In Cuba the rumba is

an athletic

exhibition dance requiring an enormous expanse of space and

an amount

of inspired wriggling that would reduce the average American

dance

floor to something resembling a choreographic hockey

arena. Its

music is fast and extremely furious. The dance that

Americans

have imported under its name is also authentically Cuban,

but it is

known in Cuba as the son (rhymes with "tone"). The

misconception

started when the Marks publishing company issued The Peanut

Vendor as a

son and found its bewildered customers arguing at retail

music

counters: "Must be a misprint. Whaddaya mean,

‘song'? The

directors of the Edward B. Marks Music Corp. immediately

went into a

huddle and decided to call it a rumba instead. And to

unsuspecting Americanos it has remained a rumba ever since.

At the moment the son's popularity is threatened in Havana

by a new

dance known as the botacita (the little boat), and

enterprising U.S.

dance promoters like

Arthur Murray

are scurrying to Cuba hoping to find

it a new terpsichorean gold mine. As danced in the

music halls

and on the streets of Havana, it is a thing of regimental

proportions

in which throngs of happy Cubans rock from side to side in a

boat like

rhythm with their hands on their hips. Like most Cuban

dance

crazes, it can be blamed squarely on the Nanigos and where

it will all

end nobody can tell.

End of Page

Copyright

1998-2014 Cuban Information Archives. All Rights

Reserved.

[To see a full size photo, right click and VIEW IMAGE]